The full video of my presentation is available on YouTube, but if you'd prefer to read, all the sides and my speaking notes are here as well.

Good evening everyone,

It’s great to have you all here… something different to the usual Melbourne Ruby events, but I’m sure it’ll all work out nonetheless.

For those who I’ve not yet had the pleasure of meeting yet, my name is Pat Allan, I’ve been working with Ruby for quite some time.

I am in Melbourne, and so I’d like to note that I live and work on the un-ceded land of the Wurundjeri and Boonwurung peoples, part of the Eastern Kulin nations. I want to pay my respects to their elders past, present, and emerging, and all elders of communities that are on this call. We’re here to discuss both community and technology, and it is important to understand that this area - what many know as Melbourne, but also known as Naarm for much longer - has been home to community and technologists for tens of thousands of years, even though much of that history has been destroyed, and there’s still so much to learn from the First Nations people and culture.

Womenjika, in the Woiwurrung language of this land, means welcome, but also to come with purpose. I presume most of you have come along tonight with the purpose of learning - but even if your purpose is just to have some distraction from the chaos we’re all grappling with right now, it’s lovely to have you here anyway.

This evening, I’m going to talk through how to write Ruby gems… and given the medium for this discussion, I’ve a couple of requests:

If you could please keep your microphones muted to avoid any background noises, that’d be great - it just makes it easier for me to focus, and for everyone else to listen. I will pause at several places in my presentation for questions - so it’s best to use the raised hand button - you can find it by clicking on the ‘Participants’ icon in the base of the window here, and then there’s the hand icon at the end of that list.

When I pause, I’ll ask each of the people with raised hands, one by one, to unmute and ask their questions (and don’t forget to mute again after that - not that I don’t love a proper discussion, we’ve just got plenty to get through tonight).

Okay, that’s the logistical challenges out of the way… so let’s get stuck into gems.

Of course, you may well be asking: what actually is a gem? Which is a very fair question… but also raises the issue of terminology, because there’s a couple of overloaded terms that I’ll be discussing. Let’s start with the word ‘gem’ itself…

This is probably the most common concept, especially for those less familiar with programming - a gem being a precious stone.

… but for anyone who codes with Ruby, you’ve probably at least heard of the concept of a gem in other ways. The main way is where a gem is a collection of code, written in Ruby, with a given purpose of some sort. There are gems that deal with statistics, gems that deal with authentication, gems that deal with searching, gems that deal with generating PDFs, gems that interact with APIs, and so on.

… but, just to add a touch of confusion, there is also the command-line tool for use in your terminal, which you use by invoking the command ‘gem’. It is part of the RubyGems package manager…

Which leads us to the second confusing term:

RubyGems is indeed a package manager - a way of installing packages of code, these aforementioned gems - onto your machine. It also handles publishing of gem versions, and removing them, and other such things…

But RubyGems is also the name of the website that stores all published versions of gems. Similar, but slightly different.

I’m hoping it’s clear through this talk by the context of what I’m saying, which gem and rubygems I’m referring to. But, if you’re not sure, please do ask me to clarify! I’ve been writing gems and using Ruby for quite some time, so I can get lost in the lingo.

This is a good first place to pause for questions - remember, via the raised hand button. Anyone?

Right, so that’s what a gem is, and some of the other terminology - but why would you create a gem?

Firstly: if you’ve got some code that does one thing quite well, and you want to use it in other projects, then it could be the perfect candidate for a gem!

And gems are - mostly - quite easy to install, so that makes it even easier to use across projects.

And also, gems can be installed and used by others - so it’s a great way of adding to the extensive Ruby ecosystem.

So, hopefully you’ve got at least the beginnings of an idea about what gems are - don’t worry if it’s not all clear yet! And perhaps there’s some understanding about why they’re useful, and why you may want to write one…

So, let’s get stuck into the actual focus of this talk: *how* to write a gem.

If a gem is just a collection of code, that’s fine, but it’s also overwhelming. Where do you start? What ties it all together?

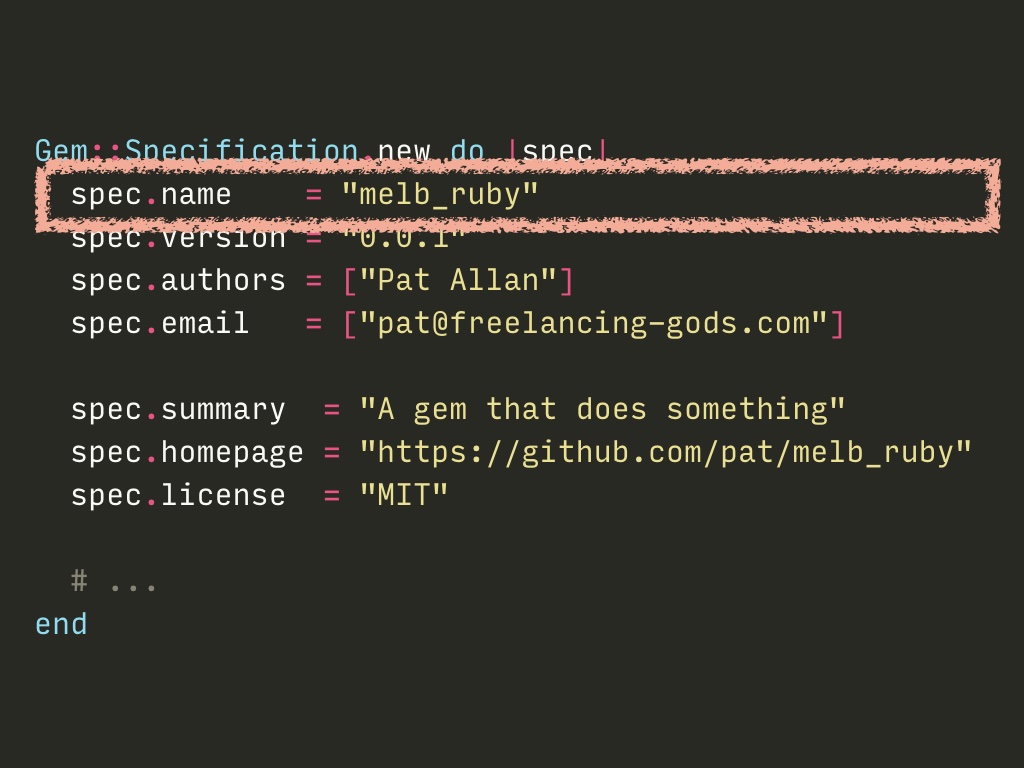

The answer is the file called the gemspec. It provides the specification for a gem - hence the name. It details what files are in the gem, what version it is, who built it, and what it depends on.

And the file extension is literally dot-gemspec. If, say, we were building a gem called ‘melb_ruby’, then you would name the file melb_ruby.gemspec.

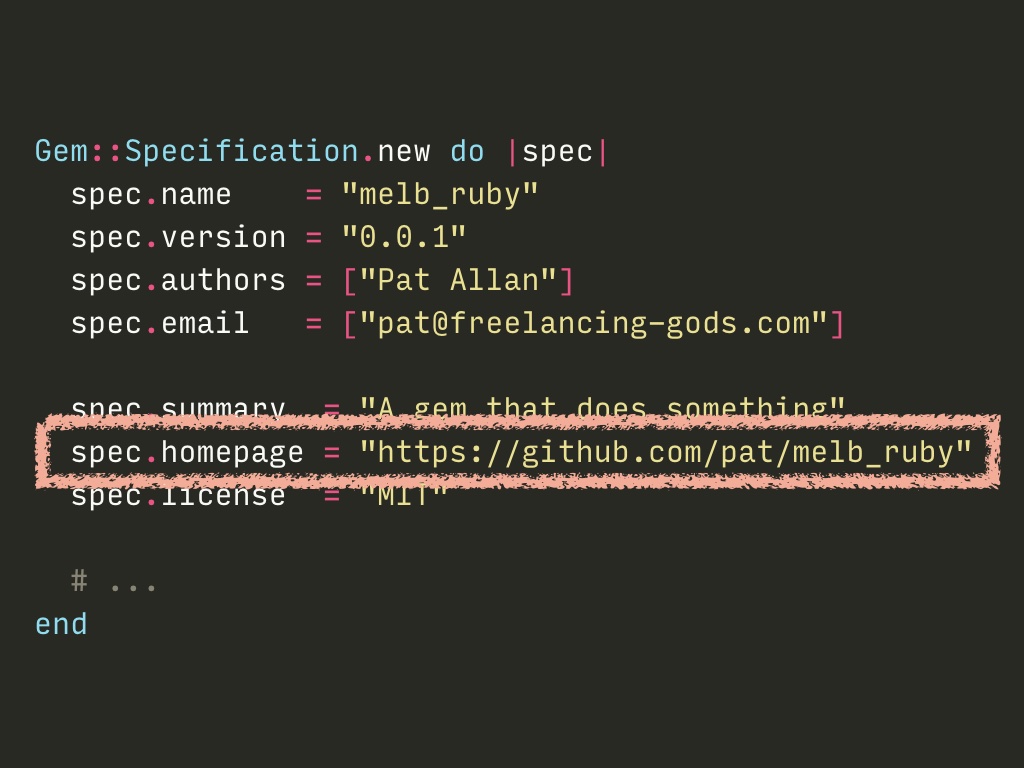

So, here's what would go in a gemspec - well, some of the core settings.

Let’s step through them one by one…

You need to specify the name of the gem…

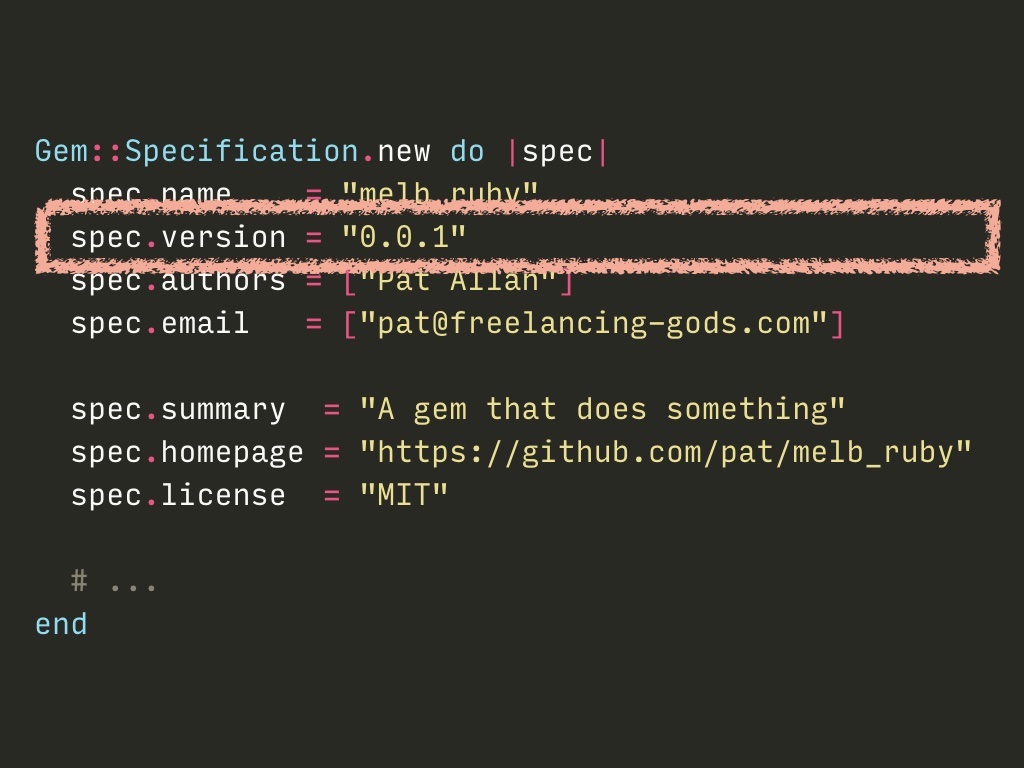

… the current version …

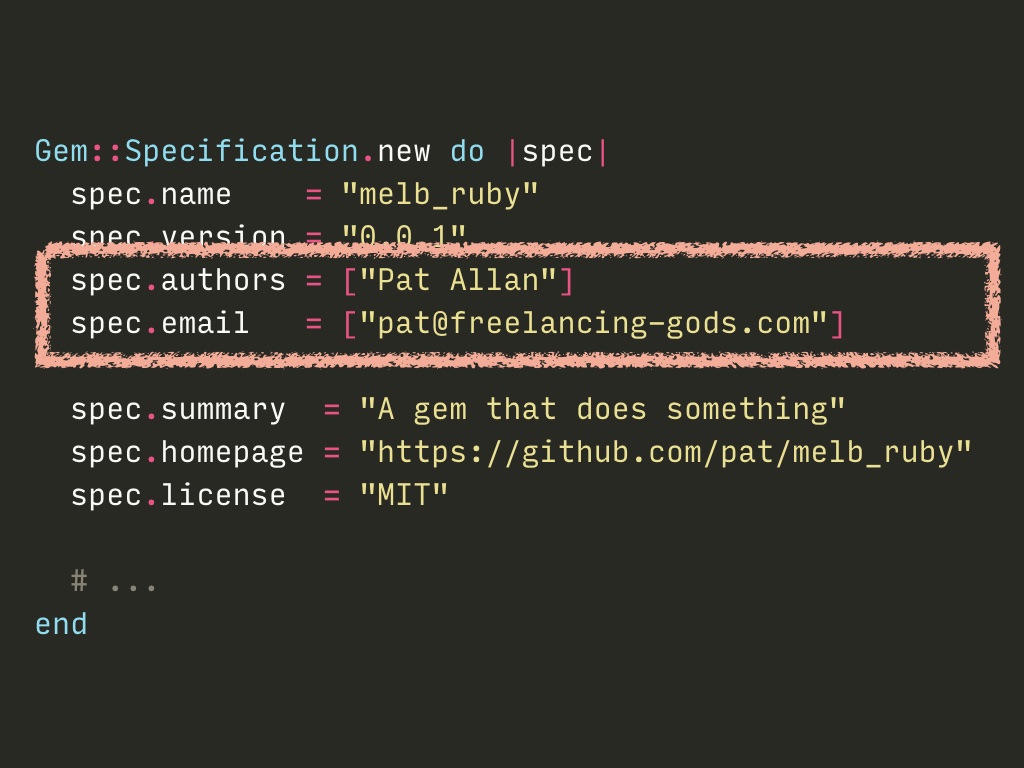

who the authors are and their email addresses

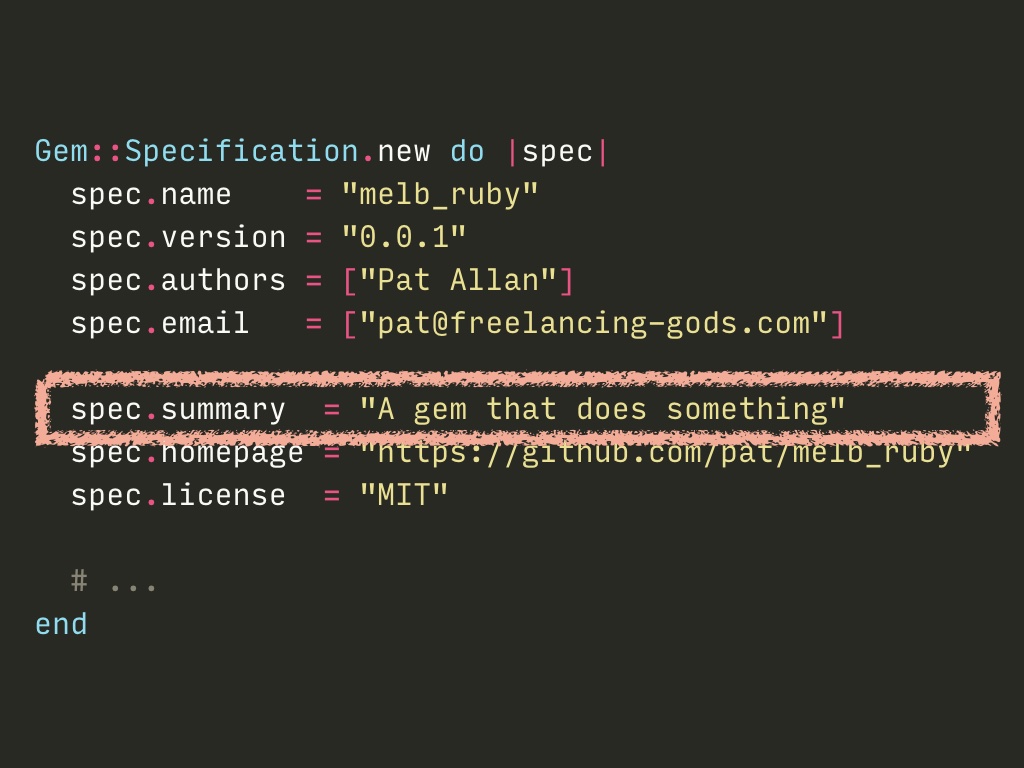

… and then a summary of what the gem does - keep it brief but to the point …

… alongside a homepage - the GitHub page for your repo is a good starting point for that.

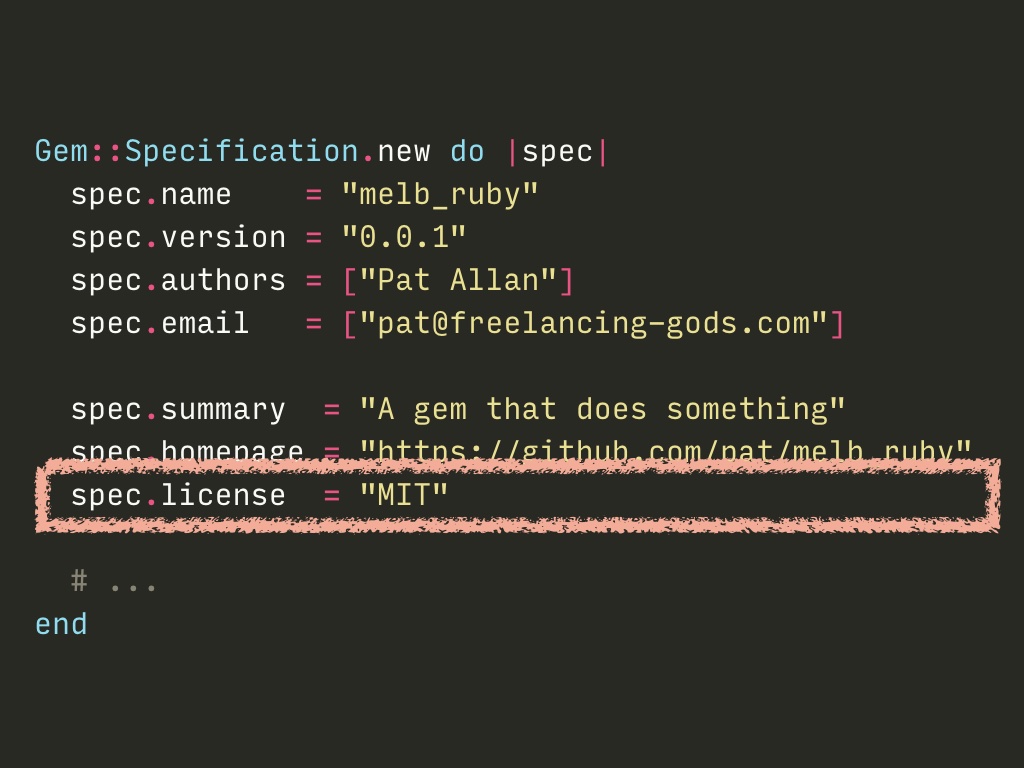

Plus, a license - I think MIT is a fine default, but I recognise that there are a lot of opinions out there, and probably a licence to fit each one. I’m not going to deal with all of that in this talk though! And besides the licence, how are people feeling about these settings thus far… any questions?

Further along in the gemspec, there are settings around where to find different files… but let's take a slight step backwards.

If you've used Rails before, you may understand that having expected locations for different types of files is super useful - the conventions help create a shared understanding of how things work together. Models, controllers, views, assets, and so on.

Gems don't have such enforced conventions for files, but some have emerged through some defaults and common community approaches.

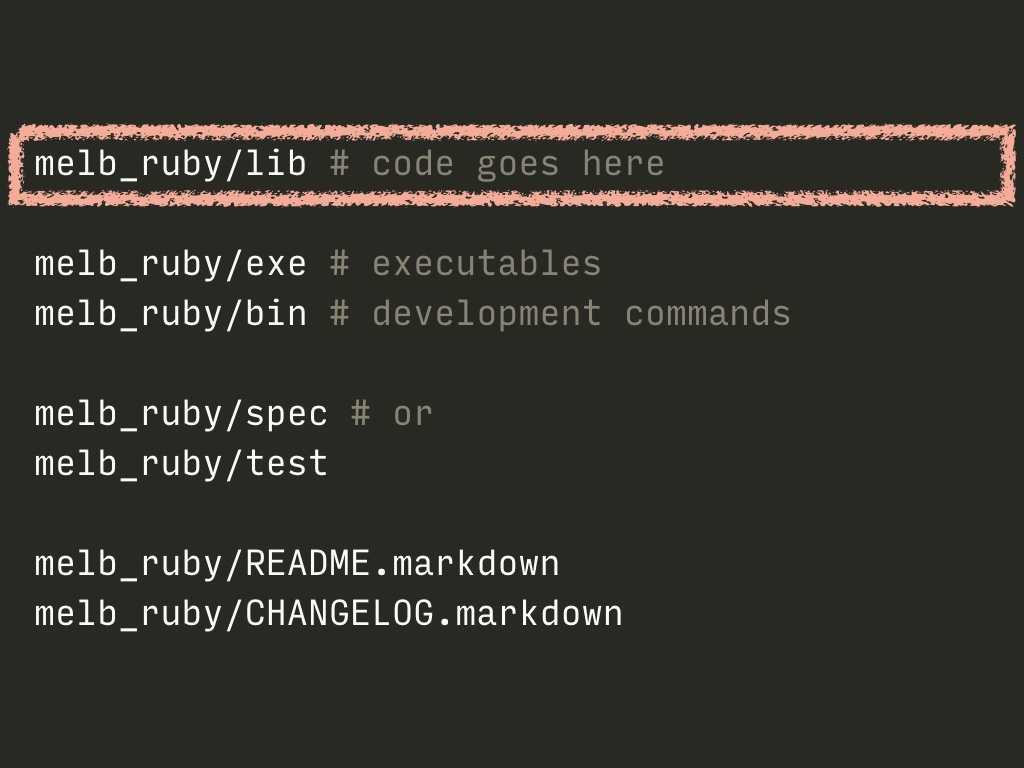

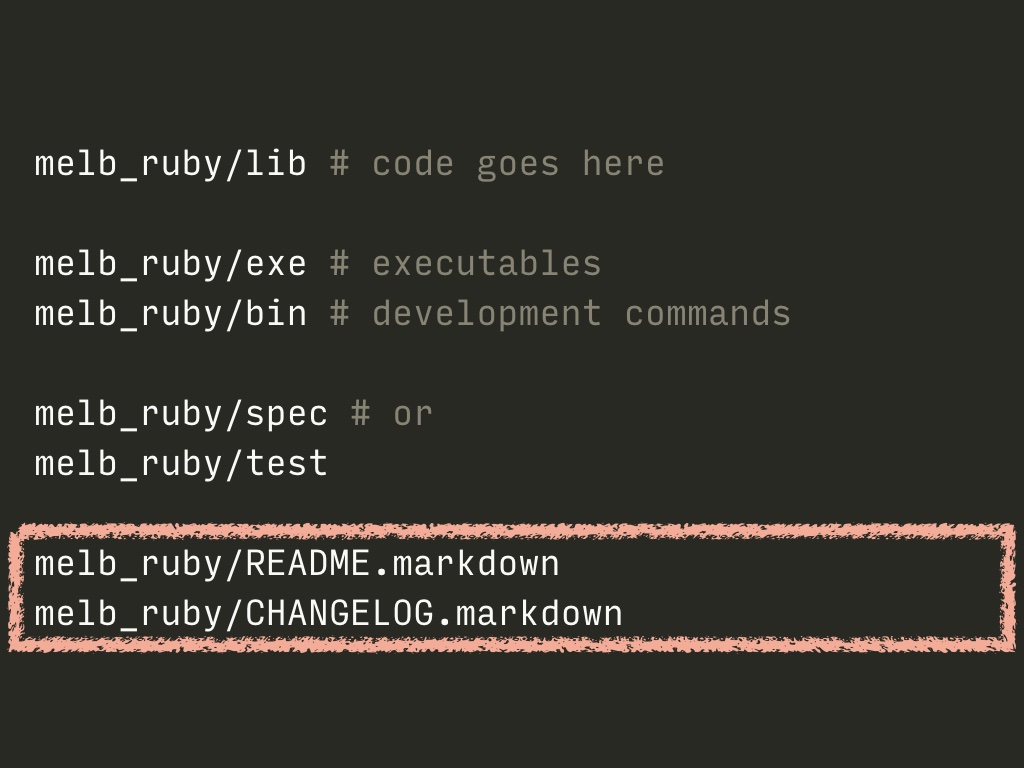

So, we’re going to put everything in a directory that’s the same name as your gem. This isn’t essential, but probably wise.

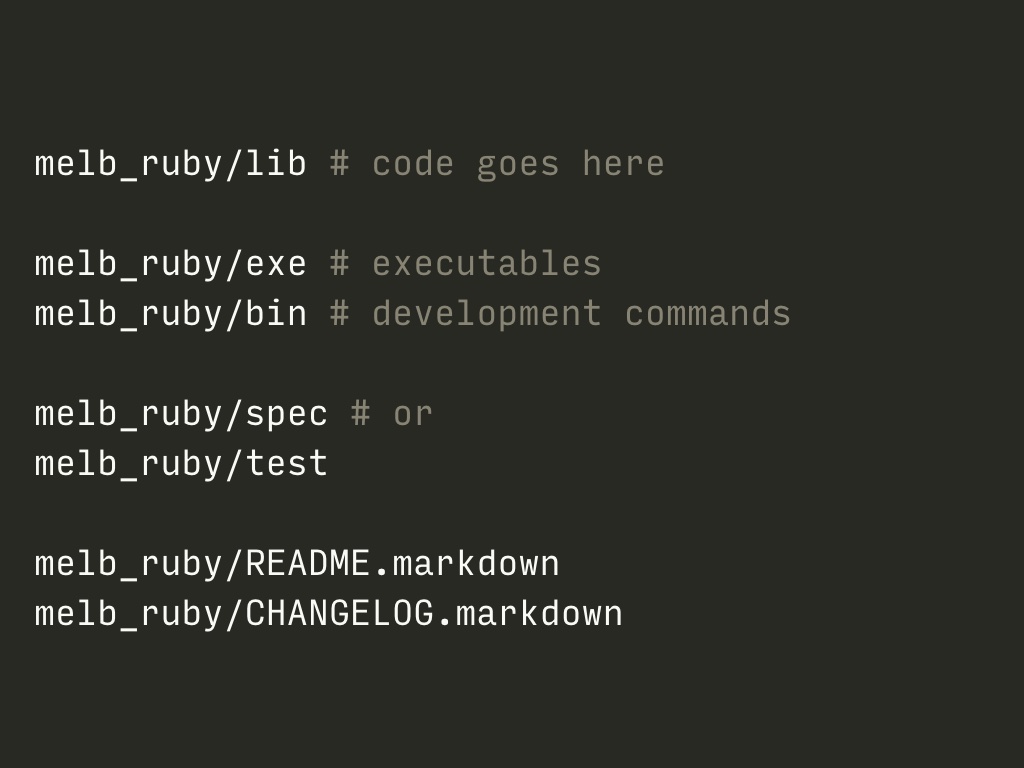

The core logic of your code should go in a directory named lib… this will likely be most of the code involved in your gem. This is the default location - you could change it if you wish, but I haven't come across a good reason why that would be wise.

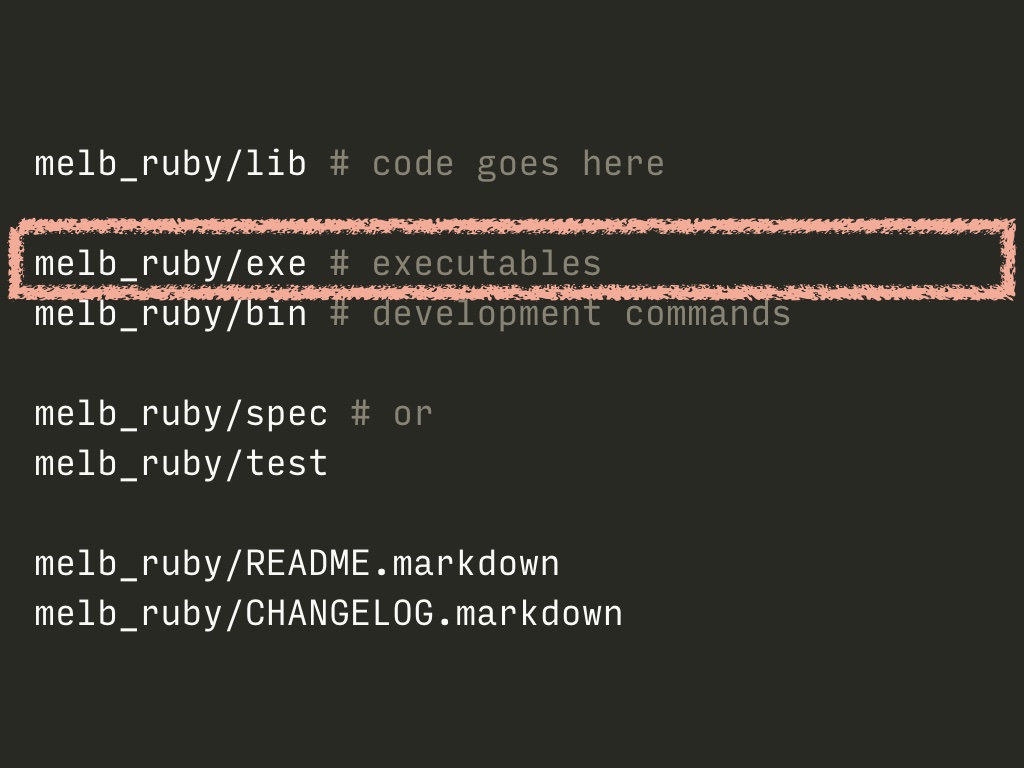

If your gem has command-line executables included in it - like both Rails and RSpec have - then you probably want to put them in a directory called exe.

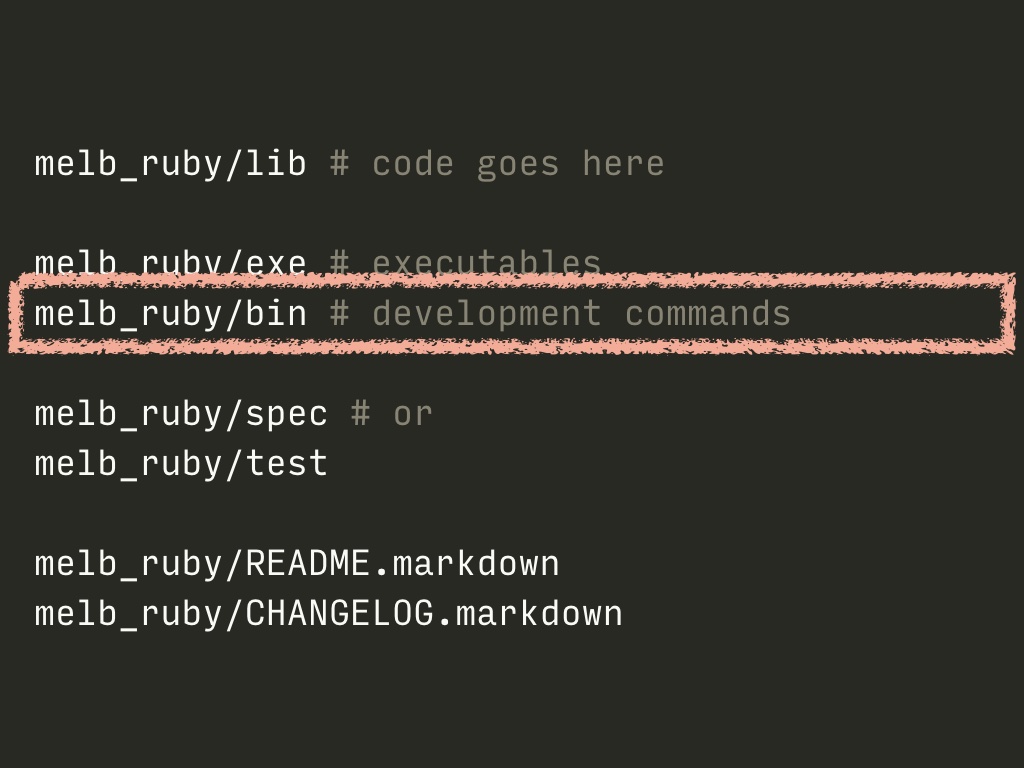

If you have any local development commands to run - binstubs and the like - you can put them in bin. If that doesn't make much sense to you right now, don't sweat it - many gems don't have either of these directories.

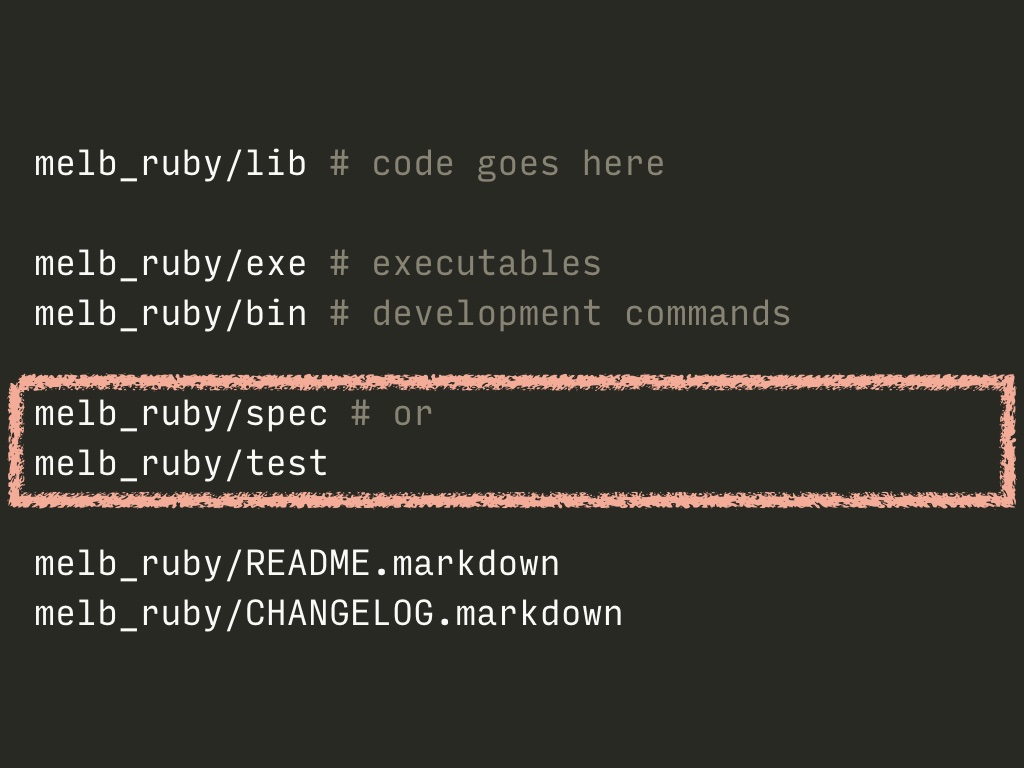

And then, your tests go in a folder expected by whichever testing gem you wish to use.

Beyond that, it's very highly recommended to document your gem with a README, so others (including your future self) know how to use it. Having a CHANGELOG helps others see what's changed over time and when - again, not essential, but recommended.

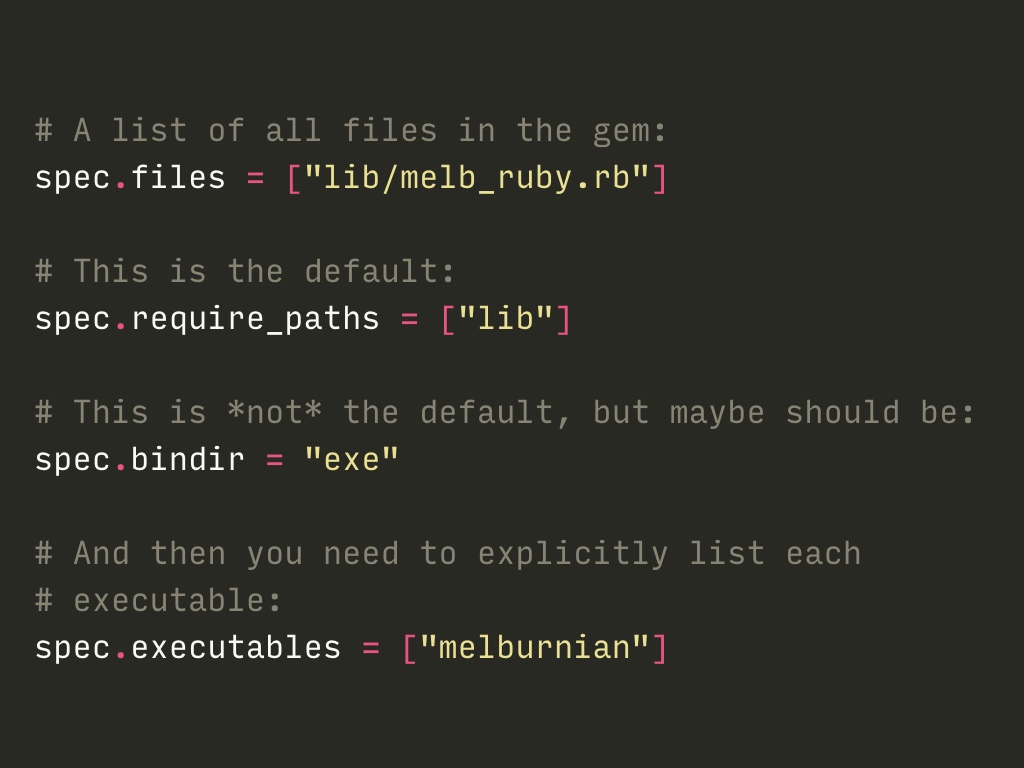

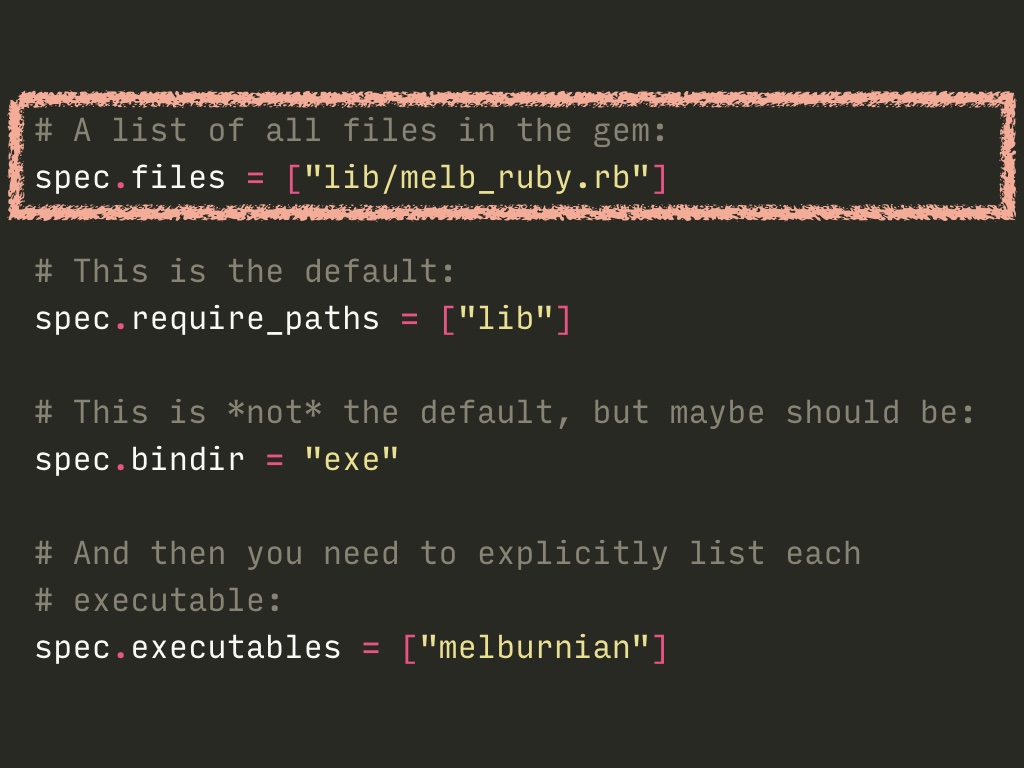

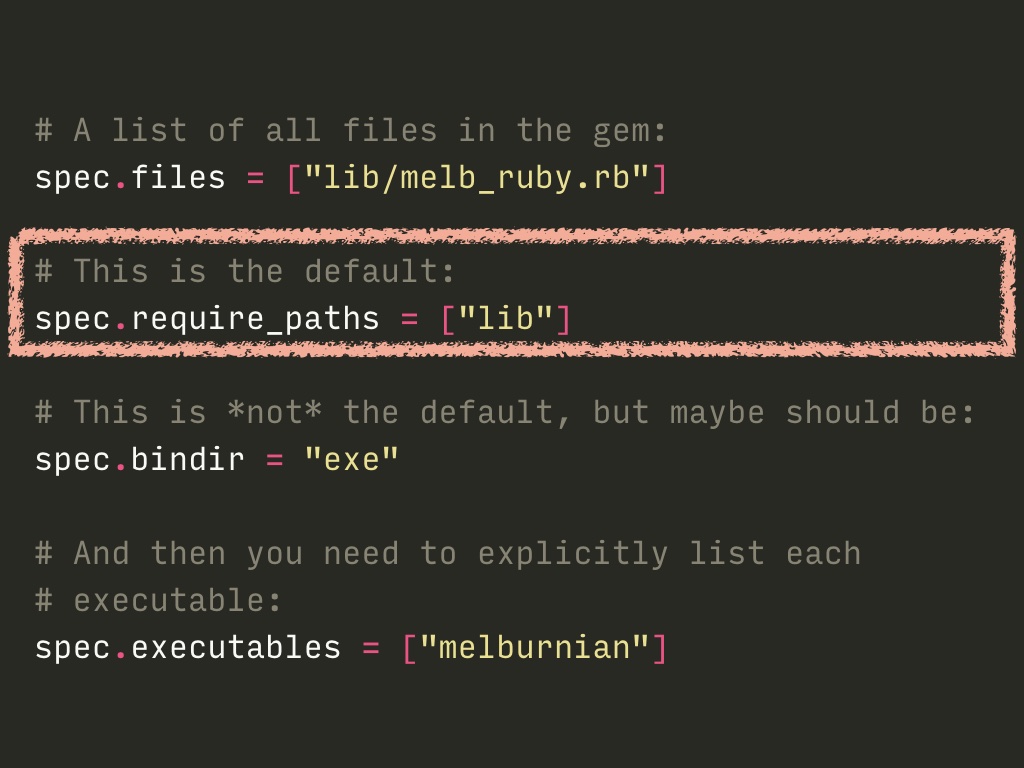

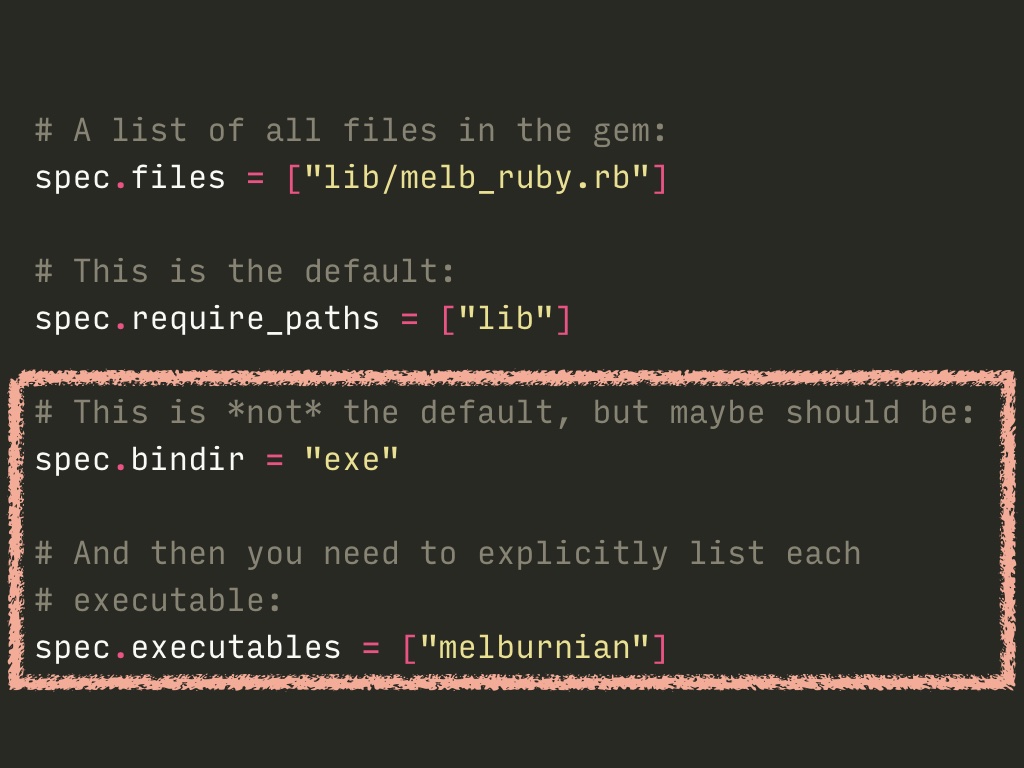

In a gemspec, you would provide information about all of these various files using these settings… again, I’ll step through it.

First, you'll need to list all the files to include in your gem. I've hard-coded it in this example, but a better approach is to automate it - let me provide another example shortly.

The `require_paths` setting isn't actually required, because `lib` is the default path already, but it's there in case you need to change things. (Please don't).

And then, for executables, you'll want to set the directory where they live, and then list each of them - not the paths, just the file names. Again, you could avoid hard-coding things here… let's look into that…

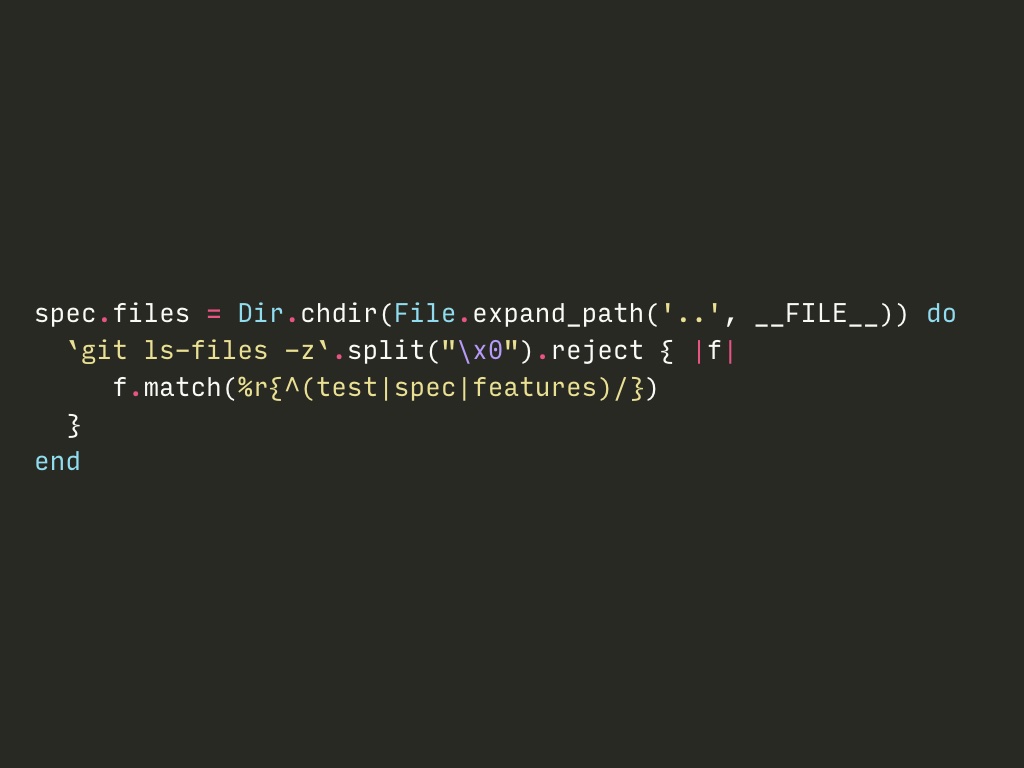

First up, here's an example of setting up the list of all files. There's a LOT going on here, so don't worry if it's overwhelming. At least, I certainly find it overwhelming…

What it's doing is finding every single file that's checked into the git repo for your gem, and then excluding any test files. Anything else that is in the folder locally but not in the repo won't be included - because you probably don't want any non-git-committed files shared beyond your machine!

This may be hard to read, but it's also much better than every time you add or remove a file to your gem, having to then edit your gemspec as well.

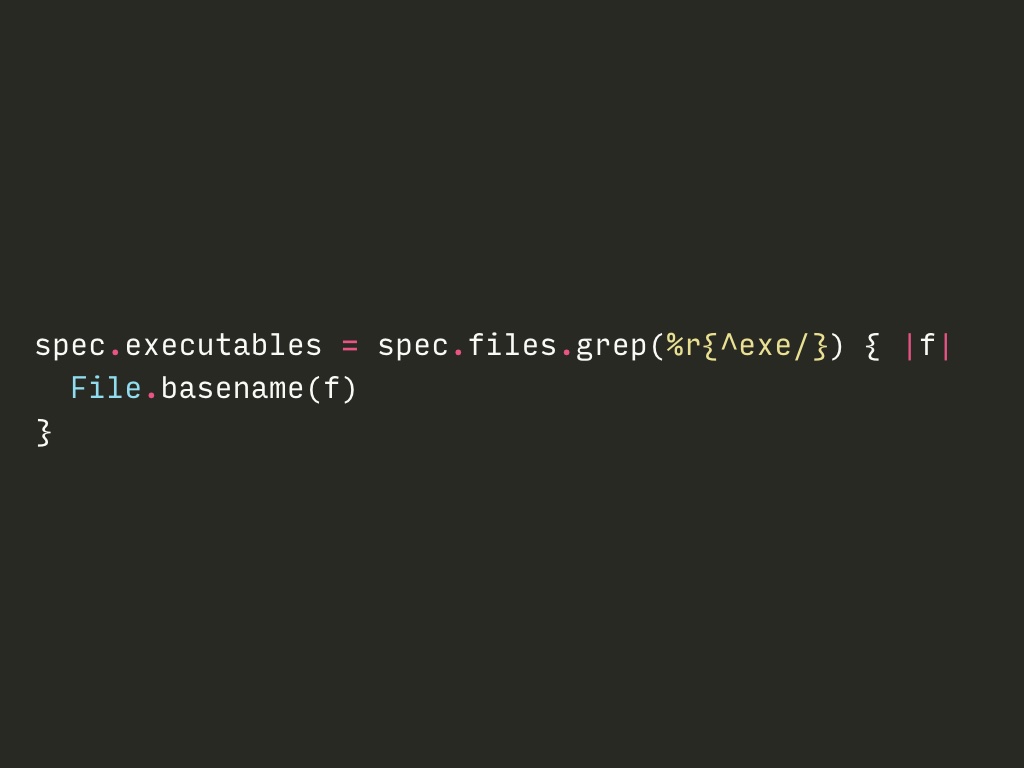

And then, similarly, here's a dynamic approach to listing the executables. It makes use of the already-compiled list of files from the previous slide, rather than having to construct the list via git-committed files again.

One of the eternally difficult parts of writing code is especially true when writing gems. Firstly: what do you call your gem? And what if that name is already taken? And then how do you name your files?

Okay, maybe I stress about this more than most, but still…

I can't tell you what to name your gem, unfortunately, but there still are some useful conventions to note:

This guideline hasn't been applied all that well historically, but still, it's nice to aim for: use underscores between each word for a single concept.

Let's take our example gem - MelbRuby is one thing. It's the event we're here for right now. One concept, two words, so as a Ruby class we'd name it like so. And that class name, translated to a gem name…

… becomes all lowercase, with an underscore between the words.

However, if you're dealing with two separate concepts in your gem name - essentially, you're namespacing, then dashes or hyphens are the way to go. Again, an example helps:

There's a gem named Rspec-rails - and it's tied to the existing concept of RSpec. So, as a Ruby class, it's written like so: RSpec-double-colon-Rails. But as a gem name…

… it becomes, again, all lowercase, but with a hyphen between the two words.

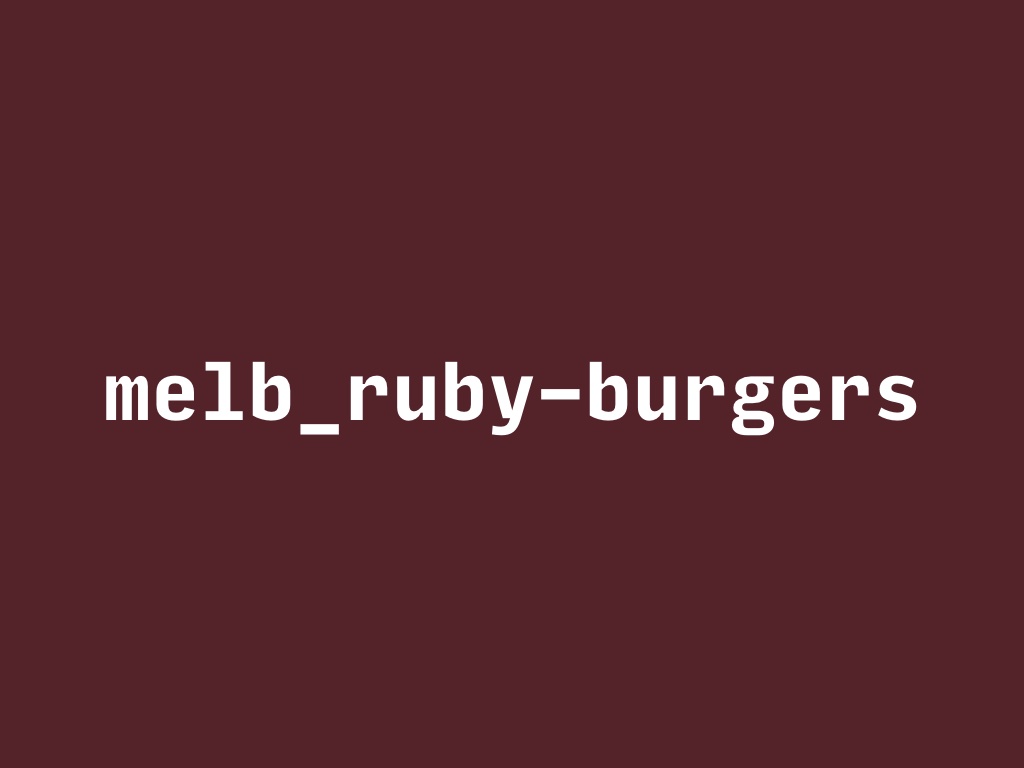

This doesn't always work out super cleanly from a naming perspective… let's say we had a new gem for a different concept within the MelbRuby namespace: Burgers - ie. the social RubyBurgers meets that had been happening regularly before this lockdown, and I'm sure they'll return once everything's a bit more normal. As Ruby modules or classes, this is relatively simple.

As a gem name, it makes me flinch a bit. Eh, so it goes…

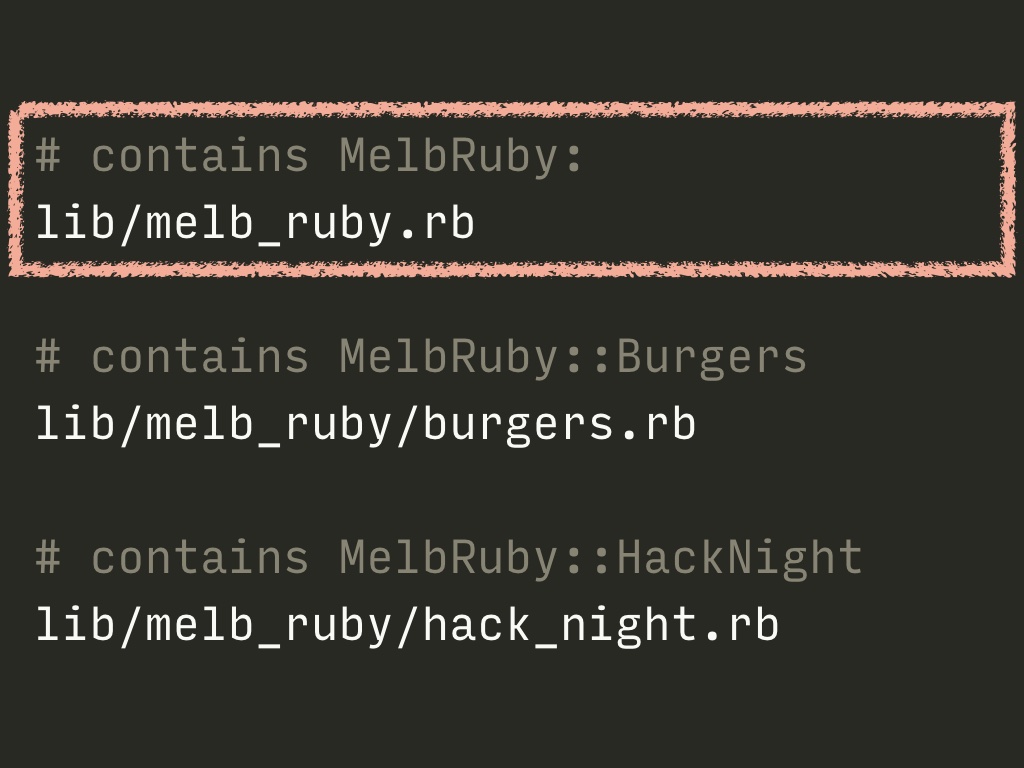

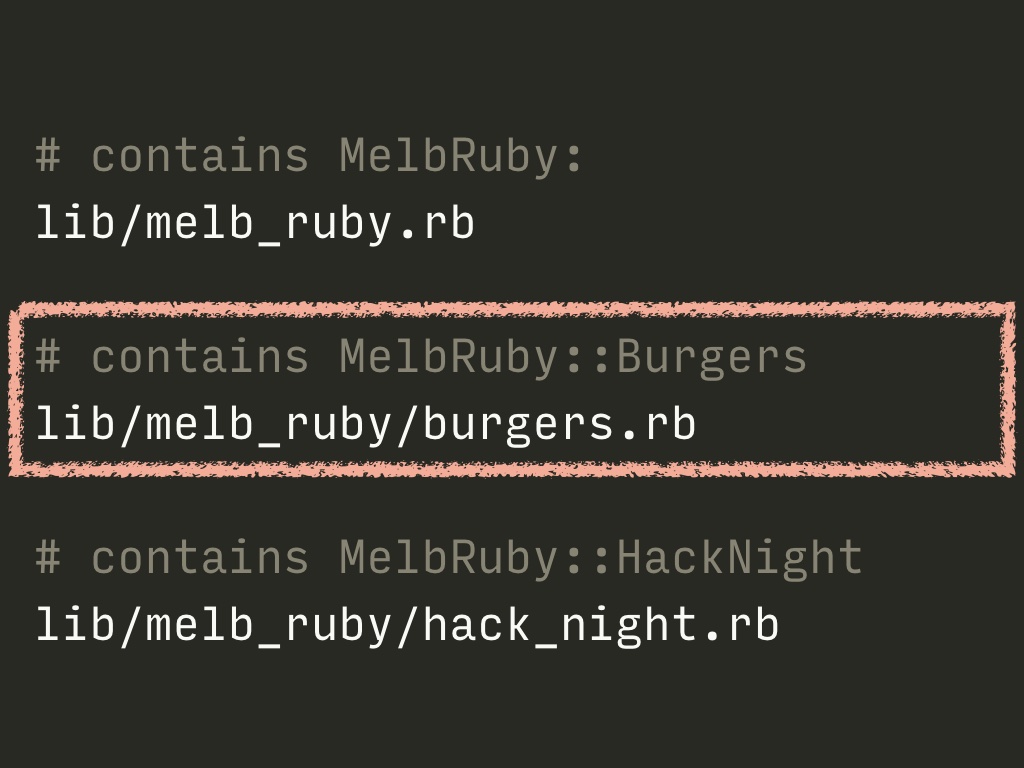

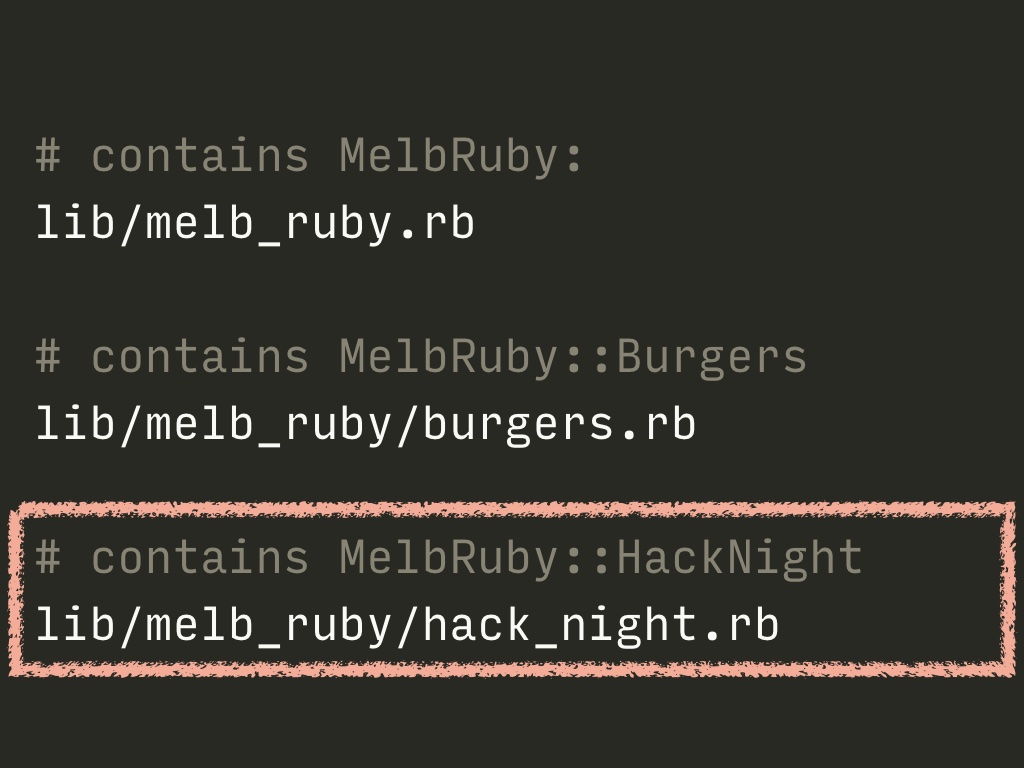

My third recommendation for naming is to ensure the file structure matches the gem name.

So, some examples of file names and their Ruby class or module equivalents.

The core file of the gem goes directly inside the lib folder, and matches the gem's name.

A namespaced gem would have a folder for the namespace in lib.

And you can follow this pattern for other namespaced constants as well.

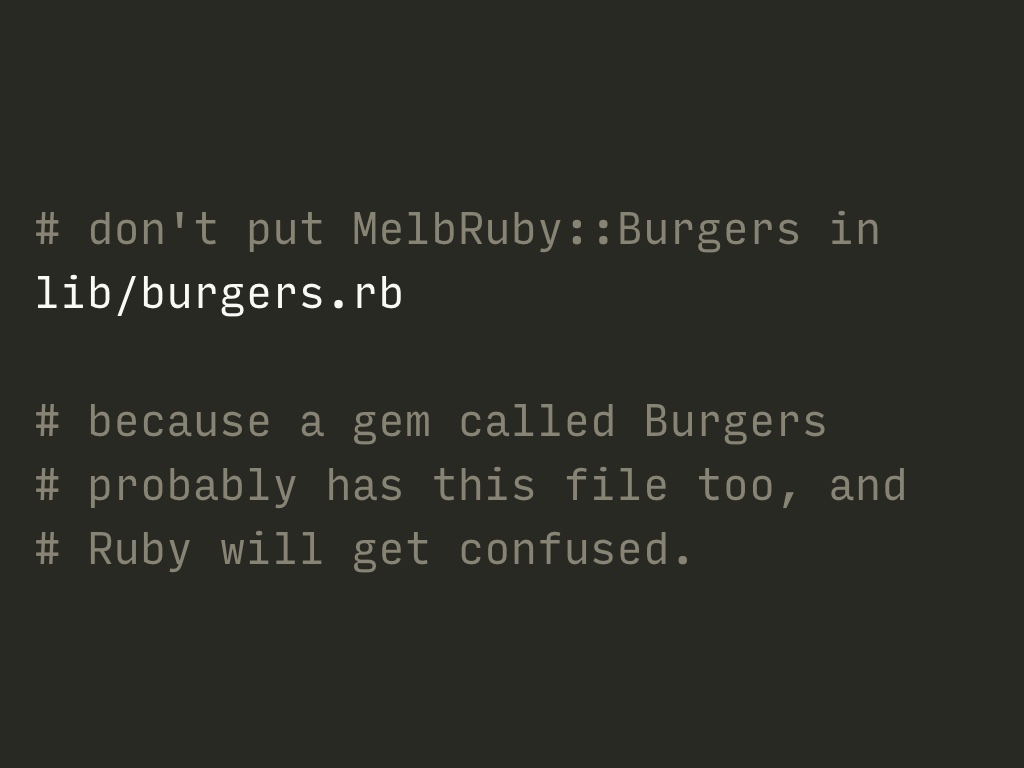

It's important to have your namespaced constants within the appropriate directory structure. You don't want to use a name that other gems - or Ruby itself - have used at the base level, because then Ruby will get confused.

So, if you're using a gem called Burgers, it will have lib/burgers.rb in its own files - but if you add the same in your lib folder, then Ruby won't be sure which to load.

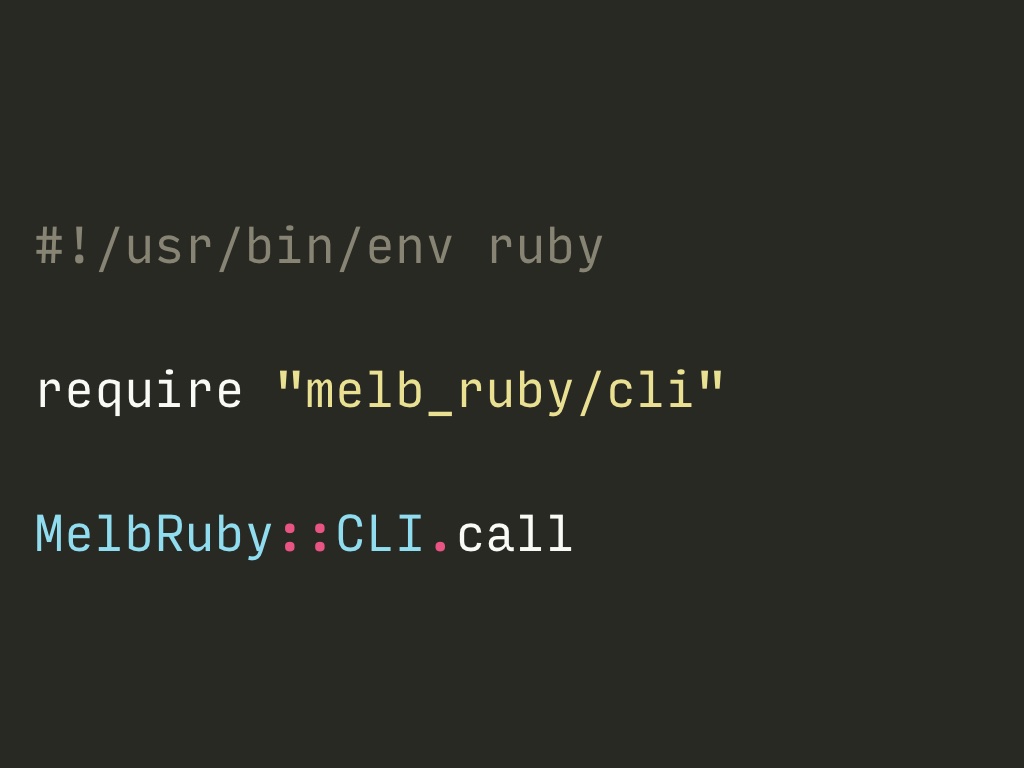

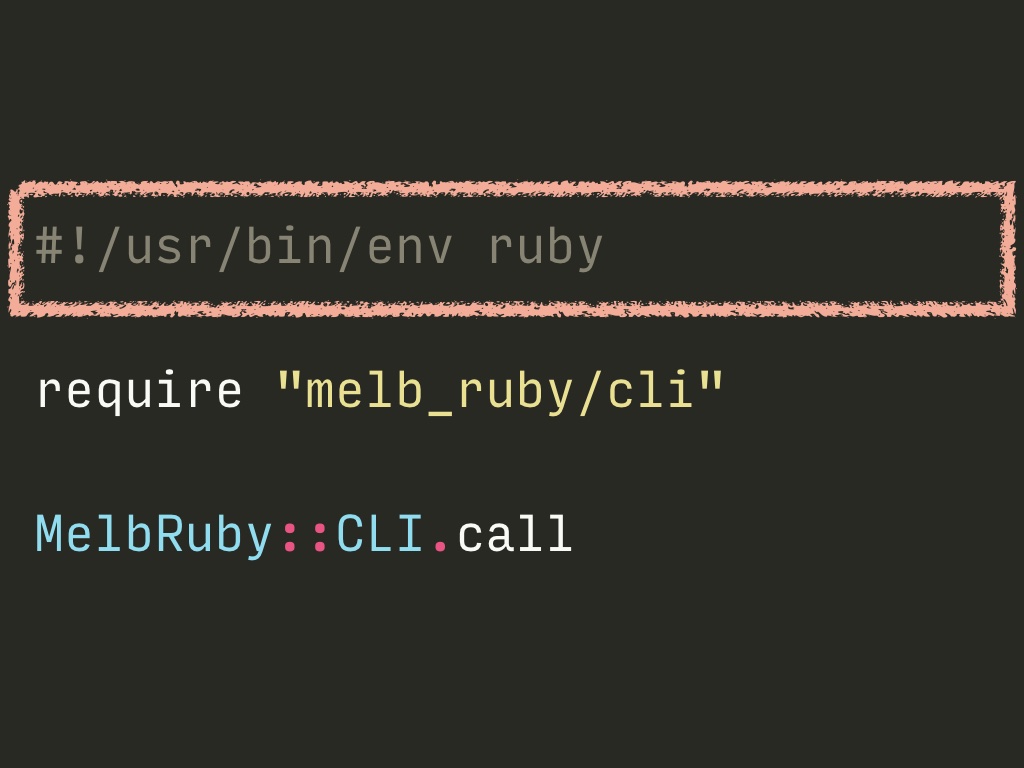

And if you're building an executable file, you would structure it something like this: include the shebang line at the start, then require what you need in Ruby, and use it. This file goes in your exe directory.

You don't want to keep any logic here - let it use code in the lib directory instead.

Oh, and for those who aren't familiar with such things - this line here is known as the shebang - which is because of the first two characters - the hash, and the exclamation mark, or bang. It's purpose is to tell your operating system how to interpret the file. In this case, we're telling it to use Ruby. Other languages would have different shebang lines at the top of their files.

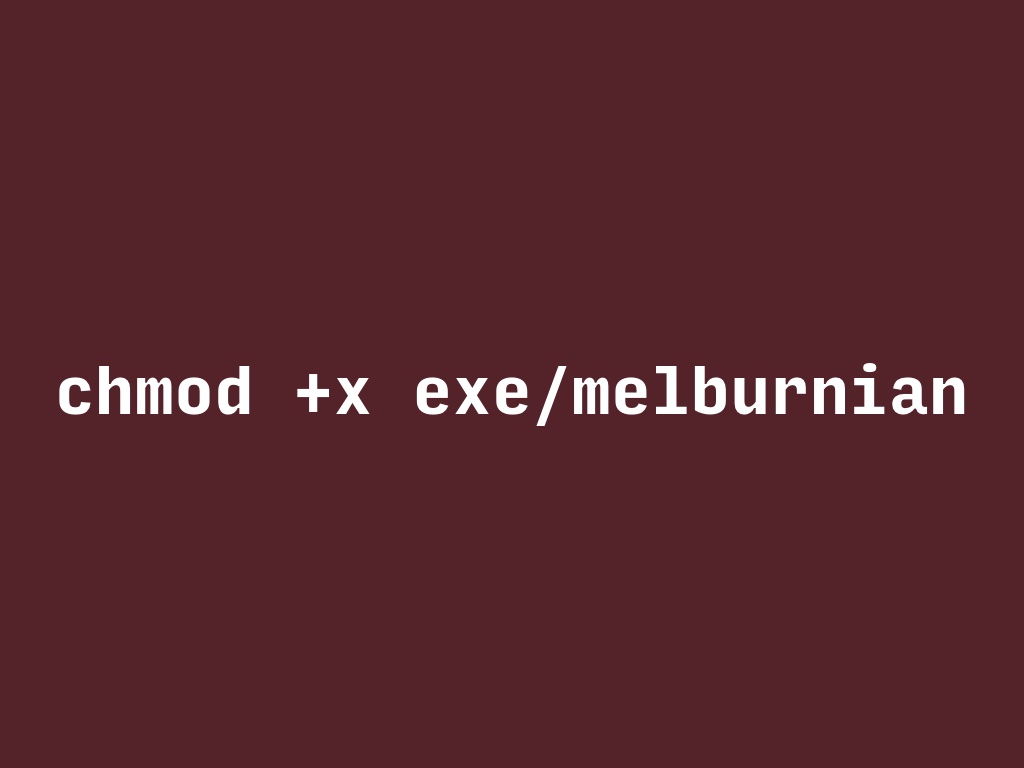

This is what you might name that executable file. Note that there's no file extension! It's like when you run a rake command in your terminal - you're not typing rake.rb, just rake. This is the same here.

And you'll need to make sure that your operating system knows that this file can be executed - that it's a program, essentially - rather than just a file to read.

This chmod command is for Mac and Linux systems - I'm not sure what the Windows equivalent is, I'm afraid. The +x is saying "add a note to this file saying it's executable"

I'll pause for a moment now - does anyone have any questions?

Okay, there's one other essential part of a gemspec we need to cover: dependencies.

This is where you're saying: my gem needs these *other* gems to work. And there are two different types of dependencies…

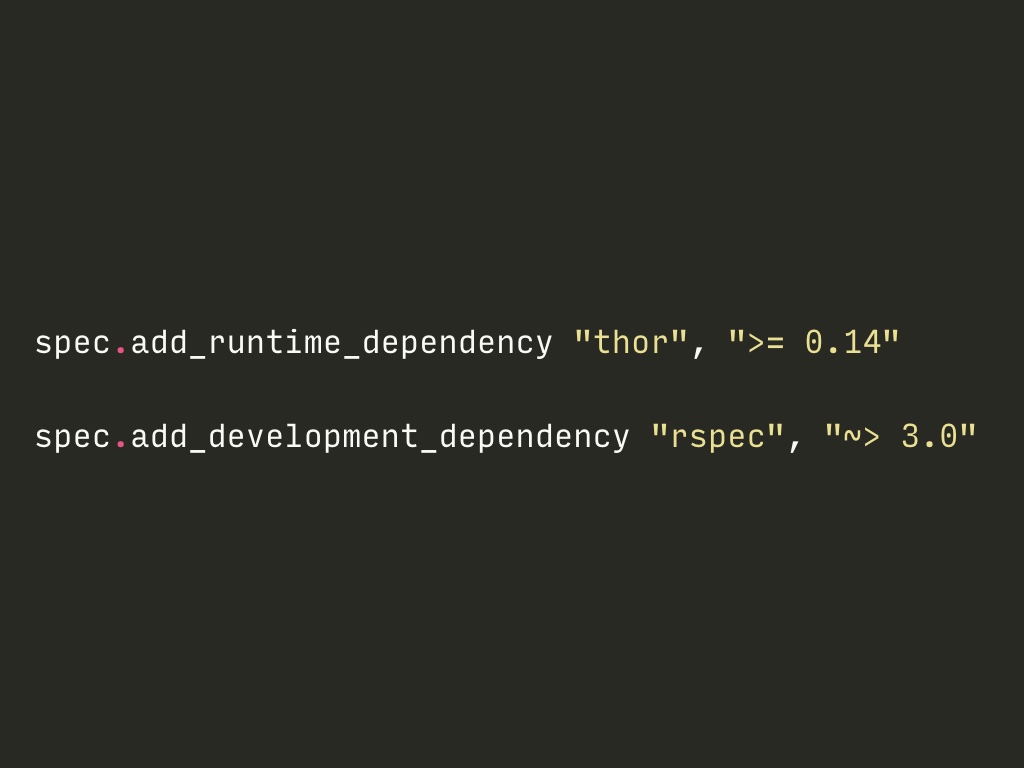

The main type is runtime dependencies - these are other gems you need for this gem to do its thing. They are essential.

Then there are development dependencies - which are only needed if you're working on the gem. Usually these are things like testing libraries like RSpec.

And in a gemspec, they'll look something like this: specifying each dependency, and the versions allowed.

Being clear about versions can be challenging - it depends on the gem itself, and how often you think it may change. There's a balance between being too specific - because if a dependency releases a new version, you probably don't want to have to issue your own new version with updated constraints every single time … or too broad, and then a significant upgrade to a dependency may not work at all with your gem.

There's nuance there to work through, but I'm not going to go into detail on that right now - but happy to talk about it after the presentation, especially if anyone has specific examples in mind.

Okay, so, let's say you've written your gemspec, and all of your files, and you've even got some tests too. Wonderful! But what's next?

Well, first, you need to package it all up into a single file…

That file has the .gem prefix, and will have the gem name and the version. It's a glorified TAR file, but we really don't need to care about the internals, we just need to build it.

The `gem` command-line tool can do this for us - and it'll make sure the gemspec is valid before doing so, which is very helpful of it.

And then this gem file can be used to install the gem alongside all the other gems on your machine

But installing on your machine is only the first step… how can others install your gems? Well, you need to publish it on rubygems.org.

So, if you haven't already, you'll need an account there. It shouldn't take long, and it doesn't cost anything.

And then, you can run this command in your terminal to send that file up to their server. The first time you run this, you'll be asked for your credentials, but after that it remembers.

And once you've published that gem version, it's locked in. To ensure a consistent experience, they cannot be changed - if you've accidentally got a bug to fix, you'll need to publish that in a new version. The same goes for any new features.

This is to ensure that no matter when someone installs a specific version of a specific gem, they will always get the same code.

It is, however, possible to remove a published version of a gem - this is known as 'yanking'.

This is not recommended… the only cases where you should is when there is a bug that's going to cause significant damage - like, removing all files on a machine, or logging passwords from other services, etc. Nefarious things, that have actually cropped up when people's credentials to Rubygems have been hacked, with new dodgy versions of gems being published.

But I believe in you all, and you're going to write decent code - even if there are bugs, because we all do that - so don't use yank.

Also, Rubygems has Multi-factor authentication - tokens are required for every time you publish a gem version - and I highly recommend setting that up.

Right. So, if you're new to this, you may be feeling a little overwhelmed. Completely fair.

… and I'm sure there are questions, but before we get to that, I want to make things a little bit easier…

Bundler - a gem we almost certainly all use - has the ability to generate a gem for you. This is like generating a new Rails app - all that boilerplate code, done automatically. It sets up the directory structure and the gemspec.

This is the command - bundle, gem, and the name of your gem. You run that, you get all the default files - it's wonderful.

Bundler also provides a set of rake tasks that take care of the generating and publishing all in one task, along with creating git tags for each release. It's pretty handy. One command, instead of three or four.

I highly recommend using Bundler in this way, and especially if you're starting out on the journey of writing gems for the first time.

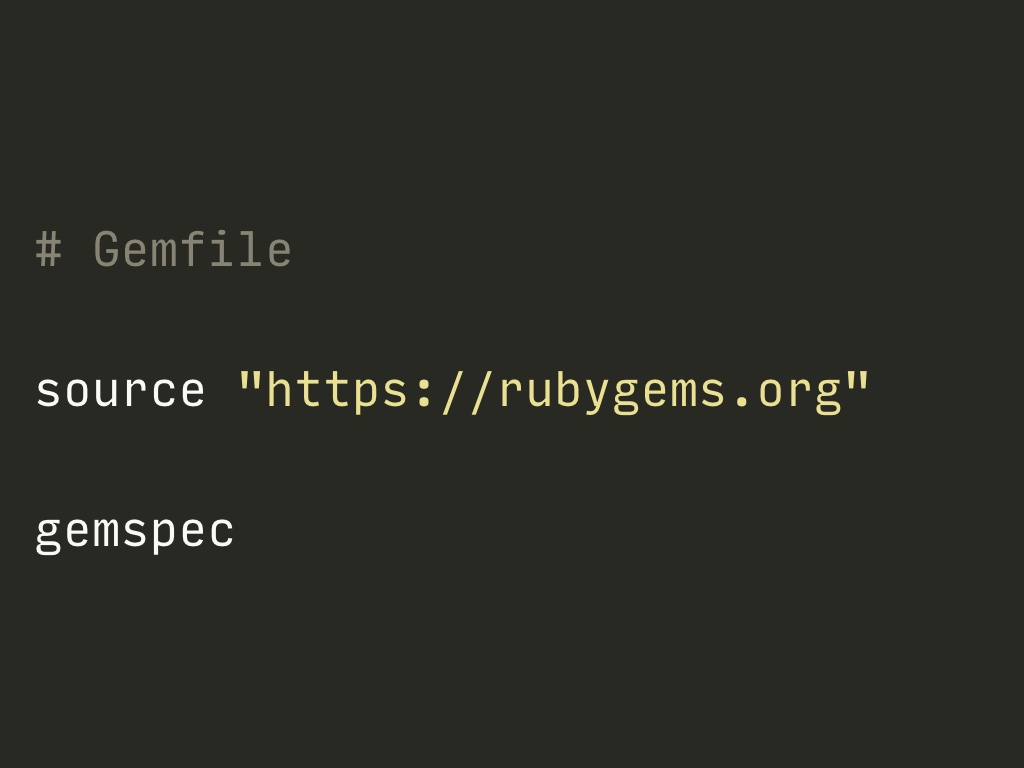

Oh, and Bundler will generate a Gemfile for you.

Gemfiles are used for specifying dependencies, but we already have that with our gemspec, right? So, bundler gives us the 'gemspec' command to load in dependencies from there. Neat.

Of course, there are times where you may have contextual dependencies - things to load only for some Ruby versions, or some Ruby runtimes. gemspecs aren't that nuanced, so those dependencies can go in your Gemfile instead. Of course, any runtime dependencies should really live in your gemspec.

How are feeling about all of this so far? Any more questions?

One thing I believe you should have with any open-source project is a Code of Conduct. Much like any event or other professional environment, it's important to set out how you expect people to behave, and how you'll treat breaches of this behaviour. Open Source isn't just the code, but also the community - contributions from others, offering support, fixing bugs, and so forth. Having a Code of Conduct is a strong step towards being clear about the industry and community we want and will work towards.

When you first generate a gem, Bundler will ask if you want to add a Code of Conduct. So, a large part of the hard work is done for you.

And speaking of support - if other people start using your gem, they'll likely be asking for help. Of course, there's no obligation for you to respond, but again - none of us work in a vacuum, and our industry is built on open-source software. So, if you can help others, that'd be wonderful.

GitHub Issues are a good place to direct people to submit bug reports and ask questions.

You may also want to suggest people ask questions on Stack Overflow, which may get a bigger audience for potential assistance.

And of course, providing documentation via your README or something more detailed is a really good starting point.

Don't feel too stressed about this - as much as we may hope otherwise, most gems don't get many users - I've written plenty where I'm pretty sure no one else has ever installed them. So, the need for support and exhaustive documentation is not high. Still, try and keep the README up to date :)

Another part of that gemspec is the version number…

… and most gems use an approach known as semantic versioning.

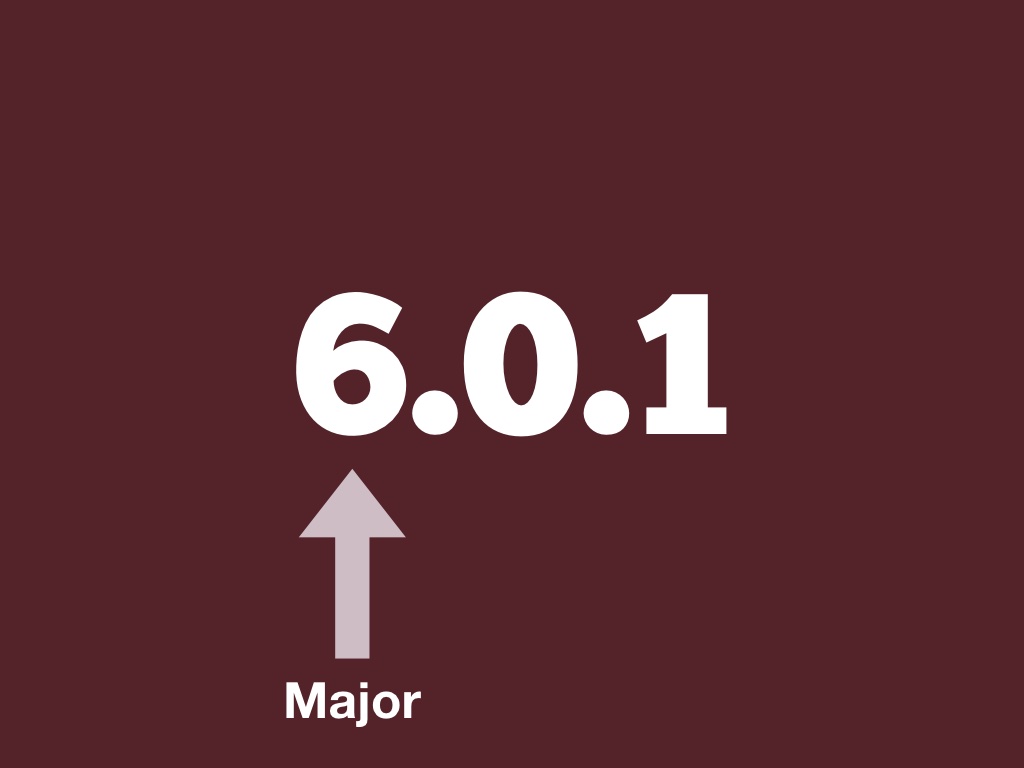

Let's take this version number as an example: 6.0.1.

6 is the Major version number

0 the minor…

and 1 the patch. You would update each section in different circumstances.

Updating the patch version should be an indication that no functionality has changed, only bugs have been fixed. Other developers should feel comfortable updating between patch versions - say, 6.0.0 to 6.0.1 - and expect no behaviour to change.

Minor version updates are a bit of a bigger deal - this is where new features can be added, but still, nothing should break. No behaviour changes, no removal of existing features.

And then Major Versions - well, in this case you can change things more dramatically. If I was upgrading a major version of a gem I was using, I'd be checking up on the Changelog and other documentation to understand whether I'd need to make any changes to my own code and how I'm using that gem.

This perhaps sounds all rather easy, but in practice I find it does require some thought, and potentially some planning ahead if your gem is somewhat popular, just to ensure other users are prepared.

And also: don't stress too much about this, especially when your gem isn't used by many people - no one gets it perfectly right. Even though that is, of course, the goal.

It's all very well for me to talk about this, but what if you want some real-world examples?

Well, almost every gem is on GitHub, so that's a good place to start…

But even better: when you have a gem in your Gemfile, then you can use the 'bundle open' command, which will open up the source code of that gem on your machine. So, if you're curious about the internals of a gem you're using, this is a great first step.

So, I feel that's the core how-to-build-a-gem stuff pretty decently covered. But I do want to address some things particularly related to writing gems that interact and build upon Rails… though first, another pause for questions. Anyone?

Thanks all. I realise it's been a long talk, but the end is in sight. Let's push through these last couple of sections… the second-last part is about writing gems that use Rails.

Some of you may have heard of Rails Engines. An engine is a gem that has its own Rails parts.

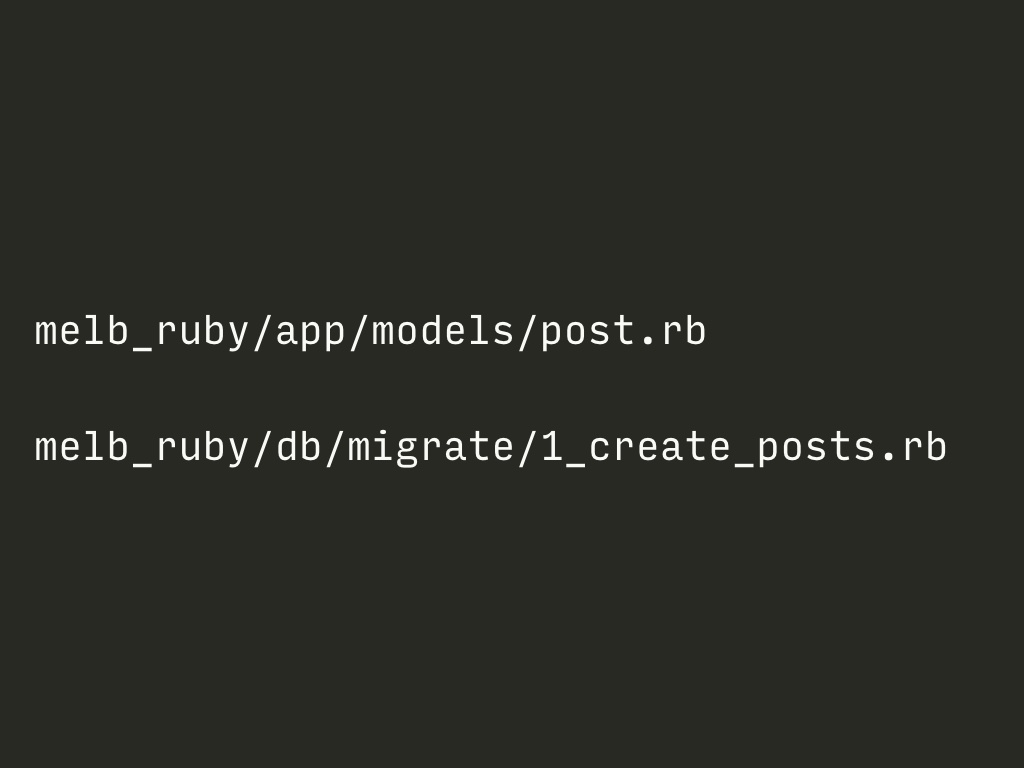

So, as well as any normal logic you may store in your lib directory, you can also add models, migrations, controllers, assets, and so forth, and you can do this within the same folders as you would in a Rails app.

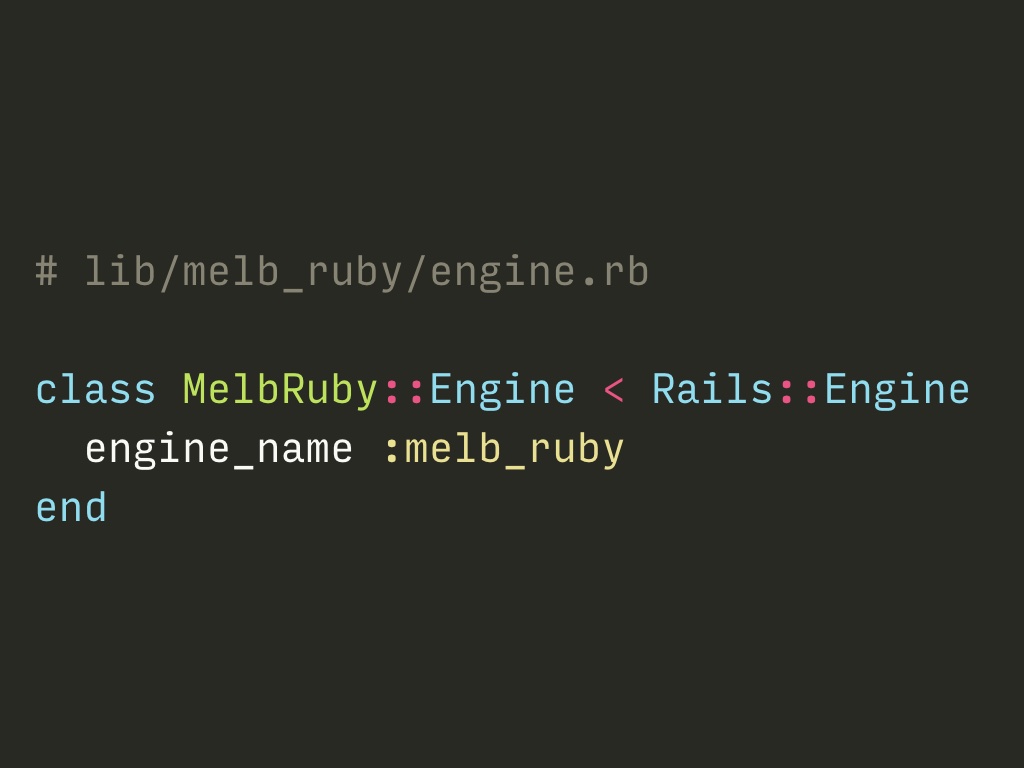

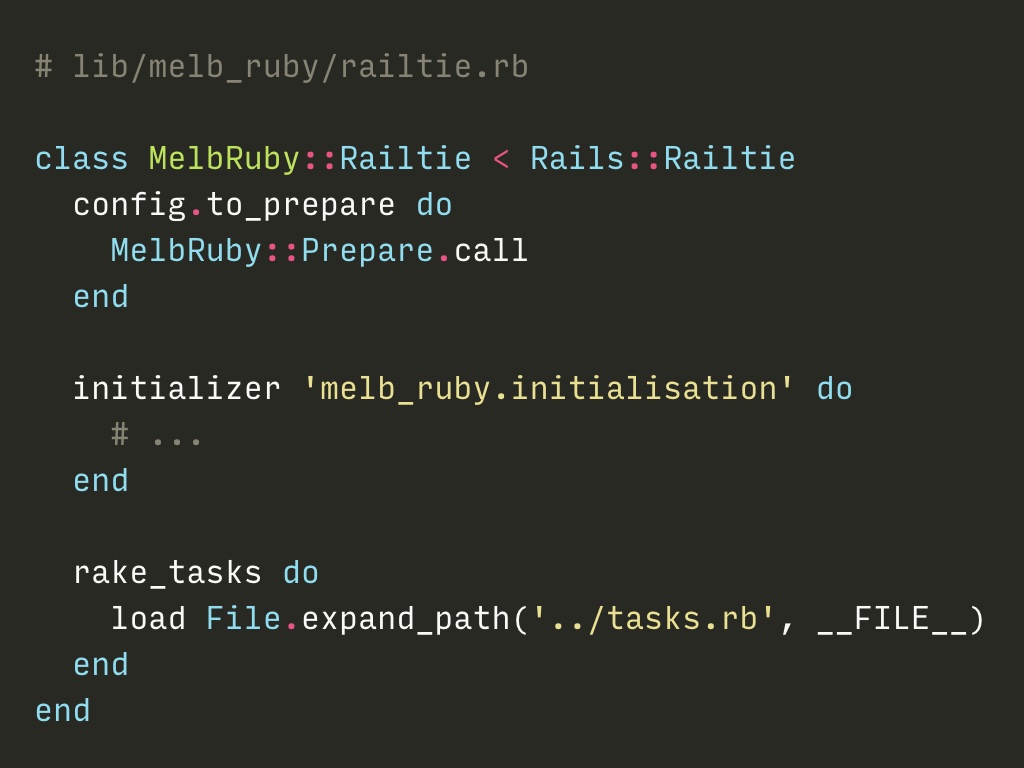

You'll need to ensure you have a subclass of Rails::Engine in your gem - here's a pretty standard example.

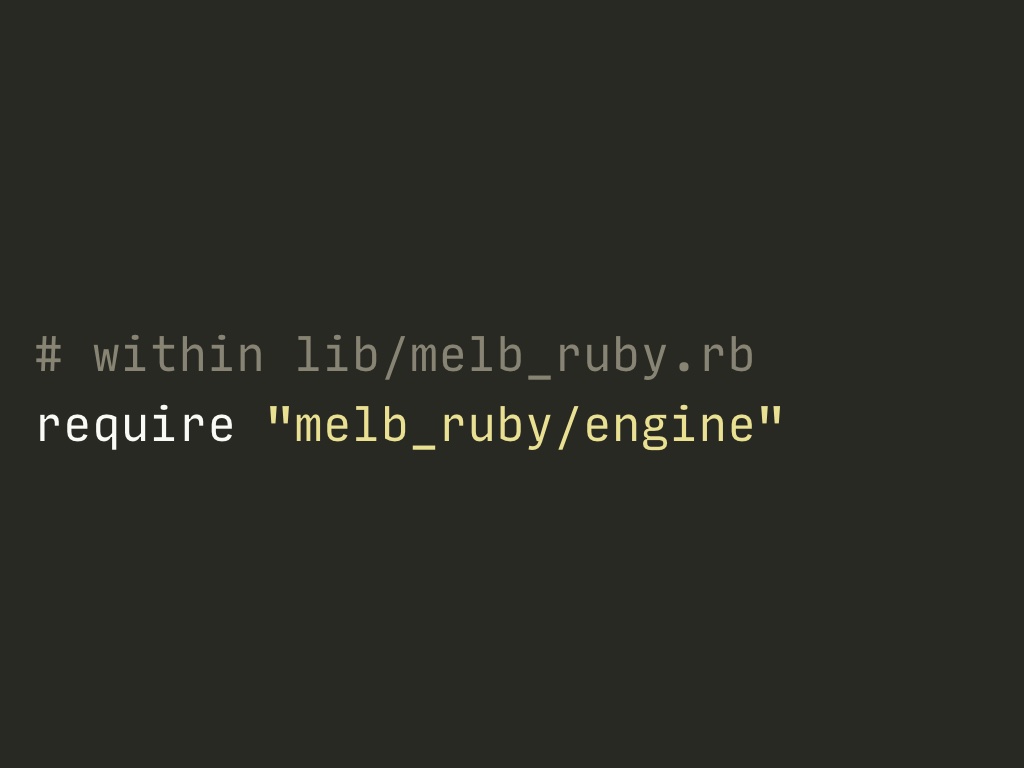

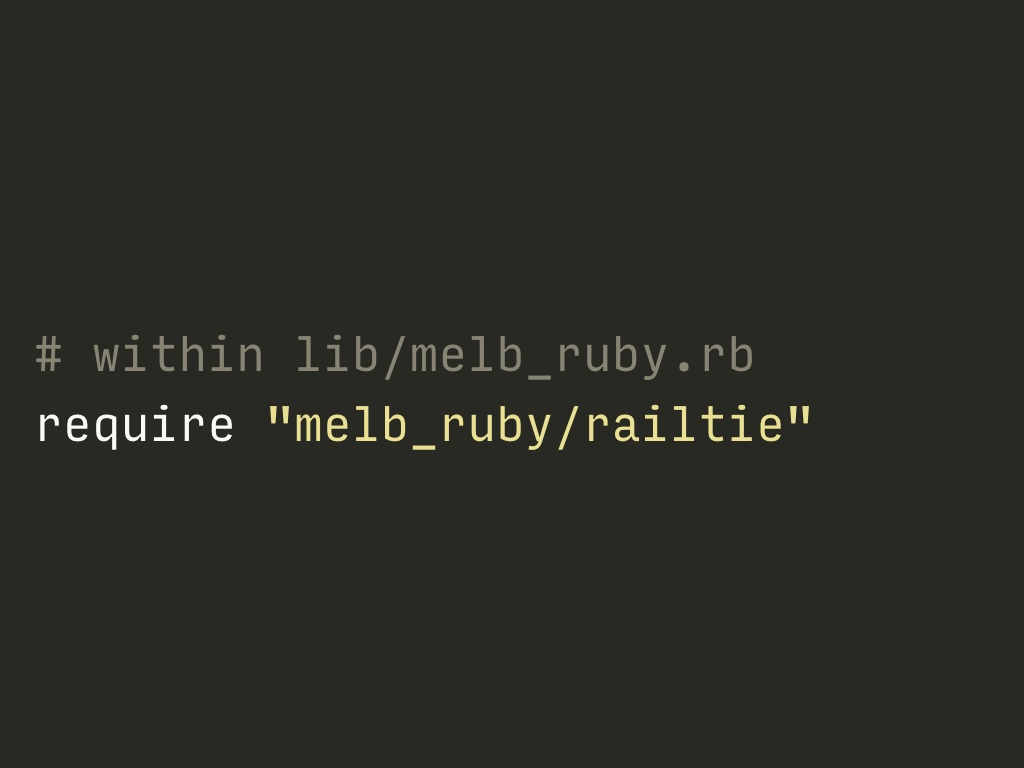

Don't forget to load that engine when the gem itself is loaded - this ensures all the Rails goodness in your gem - in those standard Rails folders - is present and picked up as your Rails app boots.

If you're not adding Rails things to other apps - i.e. no models or controllers - but you are integrating with Rails - say, if your gem works with ActiveRecord or something like that - then you may want to define a Railtie in your gem instead of an engine.

Again, you're creating a subclass, but this time of Rails::Railtie. This gives you the ability to hook into Rails' loading process, or ensure rake tasks are available within the context of your app. These situations are pretty rare, but super useful if you need them.

And yes, don't forget to load that file when the gem itself is loaded.

Oh, and for those who are particularly curious about the internals here: a Rails Engine is also a Railtie - engines are subclasses of railties.

Okay, I'm almost done. Let's just go through a bunch of various general recommendations for writing gems - well, recommendations in some cases, others are just my very-strongly-held personal opinions.

The first one I'm not expecting much in the way of argument with: don't monkey patch Ruby. That is: don't change the behaviour of standard classes or methods. It may seem useful, it may seem cool, but it's not worth the maintenance effort for you, nor the unexpected surprises for anyone else using your gem.

Similarly, don't monkey patch Rails either. This one's maybe a little less-strongly held, but there's a good chance you really don't need to do this.

I've certainly hit support requests in my own gems because other gems they are using have changed Rails' behaviour, and that's broken the integration between all of the things. Also, when Rails internals change, it becomes an extra support headache for yourself. I know that one from experience - ActiveRecord is especially painful to override consistently.

In a similar vein - use fewer modules.

Well, more to the point: I often see modules being used to include behaviour into already large classes - in particular, Rails models and controllers. They've got enough going on already, so if you can keep your logic in separate classes, I highly recommend doing so.

And sometimes it may feel like including modules is the normal Ruby way of doing things… I urge you to find creative ways around that. I'm happy to show some examples from my own code one-on-one - or, have a look at my gem Gutentag as a starting point - it's a library for adding tag associations for ActiveRecord models.

If you're writing a gem that depends on quite a wide set of versions - the prime example is Rails - and you want to ensure your test suite runs against multiple versions of that dependency: i.e. against Rails 5.0, 5.1, 5.2, 6.0… there's a gem called Appraisal that is useful for that purpose. Essentially, it generates multiple Gemfiles, and then you can instruct your test suite to run against each of them in turn.

I use Appraisal in a bunch of my projects, and it's definitely helped me stay on top of changes in my dependencies.

David spoke about this in great detail back at the January meetup, so he's also a great person to ask for help if you're venturing down this path.

If you're publishing the source code of your gem anywhere, and you're writing tests for it - which of course I recommend - then you should link it up with a CI service to run your tests automatically. Travis CI, Circle CI, and I think the new GitHub actions - as well as other services I'm sure - have free options for open source projects. Buildkite as well, if you've already got the infrastructure on hand to run your builds.

Again, it may be a bit of a hassle to set up, but once it's going, it's great - especially to run your tests against multiple versions/runtimes of Ruby.

Oh, and one bit of self-promotion - if you are writing a Rails engine, I've written a gem called Combustion to make testing engines a bit simpler. So, that could be worth trying out, if you are so inclined.

And I think that's all I've got to say on this topic for now. Hopefully it's been informative, and certainly, I'm happy to answer any last questions now, if anyone has them?

Also, if you get stuck at another point with gem questions, you're welcome to ask me on Slack or Twitter or elsewhere. I'll put these slides online and tweet/Slack the link.

Thank you all for sticking with me through to the end - you're probably sick of my voice. And thank you to Celia, Vanessa, and Ryan for making sure this meeting has still happened, with all the lockdown and social-distancing challenges we're now facing. They could have just said that the meets weren't happening until we could all gather again in-person, but they've taken that extra step to ensure the community's still connecting and learning - an amazing effort.